Geography Overview

The headwaters of the Naugatuck River, the ‘east branch’ and ‘west branch,’ originate in the towns of Winchester, Norfolk and Goshen in northwestern Connecticut before converging to form the main stem of the Naugatuck River. The main stem flows 39 miles south from Torrington through Litchfield, Harwinton, Thomaston, Watertown, Waterbury, Naugatuck, Beacon Falls, Seymour, and Ansonia before reaching its confluence with the Housatonic River in Derby, Connecticut.

The headwaters of the Naugatuck River, the ‘east branch’ and ‘west branch,’ originate in the towns of Winchester, Norfolk and Goshen in northwestern Connecticut before converging to form the main stem of the Naugatuck River. The main stem flows 39 miles south from Torrington through Litchfield, Harwinton, Thomaston, Watertown, Waterbury, Naugatuck, Beacon Falls, Seymour, and Ansonia before reaching its confluence with the Housatonic River in Derby, Connecticut.

The Naugatuck is the largest tributary of the Housatonic River, and it is the only major river in the state contained entirely within Connecticut’s borders. The ‘watershed’ that feeds water to the Naugatuck River drains 311 square miles, including portions of a total of 27 towns. By the time it reaches its confluence with the Housatonic, just 12 miles north of Long Island Sound, it is considered a ‘fourth order’ stream. This lowest section of the river is tidally influenced for approximately one mile upstream from the confluence.

A River Full of Power

As the river flows south from Torrington to Derby it drops approximately 540 feet in elevation, resulting in a relatively steep gradient of approximately 13 feet per mile. Consequently, the river is a predominantly rapidly flowing river for most of its length, characterized occasionally by rapids. The river’s size and steep gradient, made it ideal for hydropower development, causing a surge in industrial development in the 1700 and 1800’s. Unfortunately centuries of industrial abuse left the river essentially lifeless for most of the 20th century, ranking it among the most polluted rivers in the nation. Further injury was added during the mid-20th century when the river corridor was ravaged by a pair of hurricanes and then subsequently walled and dammed along much of its length. Fortunately, major changes in state and federal pollution control laws, upgrades to municipal waste water treatment plants, natural and intentional dam removal, and the transition away from heavy industry in the Valley have all contributed to vast improvements in the river’s water quality and wildlife population.

Courtesy: Naugatuck-Pomperaug Chapter Trout Unlimited)

A Shifting Landscape

Today, land use in the watershed is quite varied. The headwaters of the river flow through a predominantly rural, undeveloped forested area. The East and West Branch of the river converge to form the main stem in Torrington, the first urbanized section of the river as you move downstream. From Torrington south to Thomaston the river flows through a landscape dotted with rural, agricultural and suburban sections. From Thomaston south, however, the river landscape becomes distinctly urbanized, most notably as it passes through the city of Waterbury. The exception lies in an approximately 2-mile region located between Naugatuck and Beacon Falls. Here, the river is walled by steep, forested hillsides, inhospitable to development. This region serves as a reminder of what the stunning river valley likely looked like before the Valley’s industrial revolution left its lasting footprints.

History

Yesterday’s Naugatuck: Battered and Bruised

Beginning in the 1700’s, the Naugatuck Valley became attractive for industrial development. The tributaries and main river was used for industrial water supply (water power) and for the disposal of wastes. Because of its steep gradient, the Naugatuck River was well suited for waterpower and it was developed for this use very early in the history of Connecticut. Industrialization of its valley and use of the river as a receiving stream for municipal sewage, and a wide variety of industrial wastes followed. In 1845, the largest brass mill in the United States was built in the City of Waterbury and by the early 1900s the Naugatuck Valley was one of the principal brass manufacturing regions of the world, a distinction, which remained through the 1960s.

Large quantities of industrial wastes from the brass mills and related metalworking industries, as well as wastes generated by the manufacturing of rubber, synthetic chemicals and textiles, were discharged to the river along with municipal sewage. A report by the state Sewage Commission dated 1899 stated that the Naugatuck River had reached the limit of permissible pollution due to the discharge of industrial wastes and municipal sewage. A subsequent report by the state Board of Health in 1915 described the river as badly polluted throughout its length and listed six municipal and 29 industrial waste sources on the river. This grossly polluted condition was essentially unchanged into the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Photo courtesy of the Naugatuck Historical Society

High Rock Grove adjacent to the Naugatuck Railroad.

A River Reborn

Citizen groups and communities along the river have played a key role in driving the Naugatuck River Restoration Plan forward. River advocacy groups have conducted river cleanups, fish stocking, revegetation projects, river celebrations and have volunteered to conduct water quality monitoring.

The State of Connecticut has also been a dedicated partner in the reversal of the river’s declining health. The adoption of Connecticut’s Clean Water Act in 1967 and the adoption of the federal Water Pollution Control Act in 1972, gave the State the legal authority necessary to finally address water quality degradation in the river. By 1976, through a combination of legal enforcement and the distribution of state and federal grants, all eight municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) discharging to the Naugatuck River had installed secondary waste treatment, ensuring that cleaner, safer water was discharged to the river from these plants. At the same time, industries were required to begin using “best available technology” to treat their wastewaters, leading to further reductions in pollutants entering the river. Many direct discharges of industrial and cooling water to the river were also reduced. More recently, industrial discharges have been reduced even further through the use of wastewater recycling systems which reuse discharges rather than sending them into the river.

Wastewater treatment improvements during the 1970’s, combined with the general decline of the brass industry and closure of other businesses, led to dramatic improvements in the water quality and aesthetics of the Naugatuck River. In the mid 1980s, the Connecticut Department of Energy & the Environment (DEEP, then known as the Department of Environmental Protection) took additional permitting measures based upon the biology of the river to further reduce toxic substances in industrial discharges.

In the late 1980s, the Department adopted a plan to improve the effectiveness of WWTPs in order to meet water quality goals for the river. The plan required upgrades at nearly all of the WWTPs along the river. Upgrades were completed in Seymour in 1992, Torrington in 1994, Naugatuck in 1995, and Waterbury in 2000. Thomaston’s AWT facilities are in the final stages of construction. In Watertown, the Fire District eliminated its discharge to Steele Brook, an important tributary to the Naugatuck, by linking instead to the new Waterbury WWTP, which received its own upgrades as well.

Particular emphasis was placed on improving the Waterbury WWTP, by far the largest wastewater plant on the river. Costing $124 million and taking three years (1997-2000) to construct, this advanced wastewater treatment facility features ammonia removal, total nitrogen removal and ultraviolet light disinfection – upgrades critical to ensuring continued improvements in the health of the Naugatuck River as well as Long Island Sound.

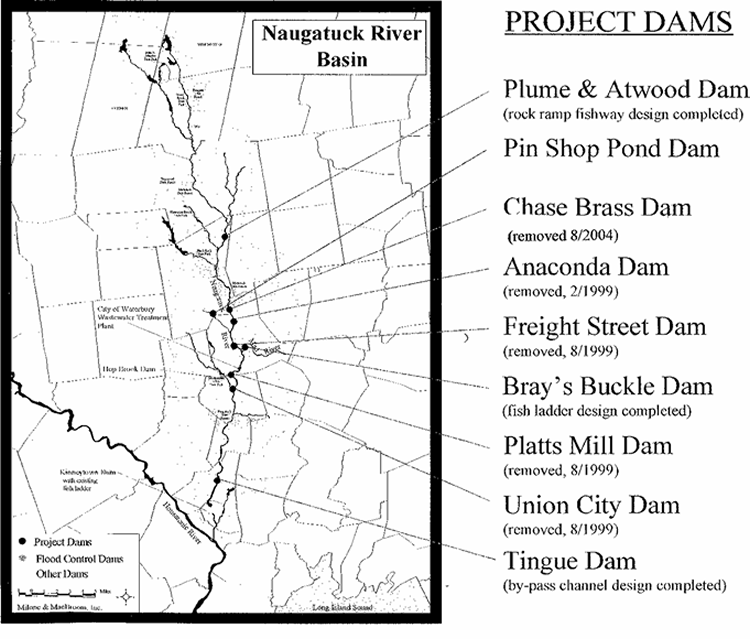

Due to its size, constructing a new WWTP in Waterbury without temporarily impacting the river, proved difficult. A plan was therefore proposed to allow only very limited treatment at the existing facility while the new plant was being built. To compensate for the negative impacts on the river due to not fully treating the sewage during this construction period, CT DEEP, the EPA and the City of Waterbury developed a mitigation plan to enhance water quality and the ecology of the Naugatuck. Among other things, the plan required removal or construction of fish passage facilities at several major dams within the watershed. In addition, eleven areas were selected for planting enhancements, which help improve water quality as well as habitat adjacent to and within the stream.

A committed program of formal enforcement actions for wastewater discharge violations, led to the collection of corporate penalties in excess of $2.5 million. These funds were reinvested in Supplemental Environmental Projects (“SEPs”) throughout the watershed. While many of the SEPs are tied to dam removal and fish passage, SEP monies have also been used to purchase equipment to treat and dispose of grease tank wastes, encourage local river cleanups and for the creation of riverside pocket parks, open space preservation, and public river access.

Photo courtesy of Michael A Krenesky